| introduction |

| background |

| role of cities |

| SA and the GCR |

| green initiatives |

| food |

| solar energy |

| energy efficiency |

| CSP |

| water and sanitation |

| waste |

| mobilising the region |

| water and sanitation |

The World Bank says there has been a six-fold increase in water use for only a two-fold increase in population size since 1990. |

|

With an average annual rainfall of 497mm, South Africa is a dry country. More problematic is that 98% of available water resources in Gauteng have already been allocated. This means that all future growth will be constrained by the lack of this resource. In addition, the country has no further ‘dilution capacity’ when it comes to absorbing effluents in its water. The Gauteng region is located on a watershed which means that outflows of waste water pollute the water resources it depends on. After China, South Africa’s national water resources contain some of the highest toxin levels in the world. In short, the combination of low average rainfall, over-exploitation and re-engineered spatial flows have led South Africa to an imminent water crisis in quantity as well as quality. |

what are we saying about water quantities? |

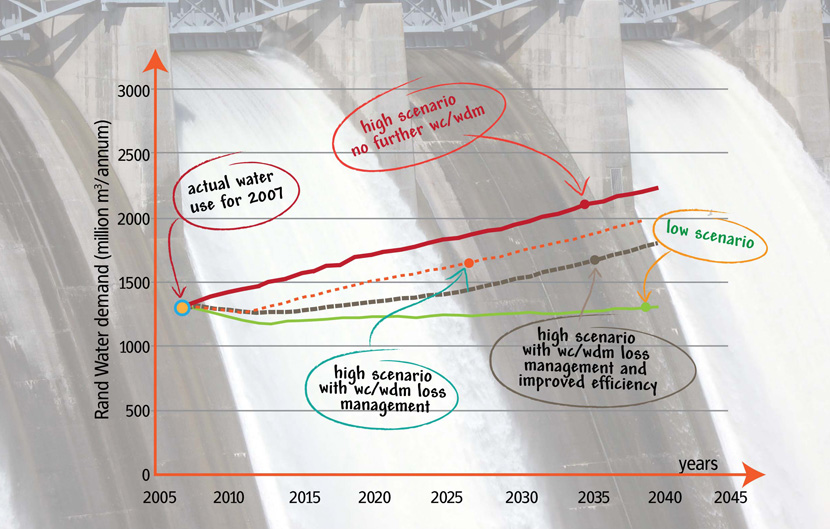

Situated on the watershed between the Orange/Vaal and the Crocodile/Limpopo river systems, Gauteng has limited natural water resources. The Vaal in the south and the Crocodile in the north have historically provided water supplies for the region, but their capacity has long been outstripped by demand which is perhaps ten times more than sustainable and reliable locally available resources. The province’s water supply now comes primarily from the Vaal, Orange (Lesotho) and Thukela (a linkage which adds reliability rather than large volumes). In terms of quantity, sources such as groundwater are of limited local importance and rainfall, while important for agriculture and maintaining the natural landscape, is relatively low and, more important, highly seasonal and variable. There is sufficient water in the Orange River system to meet the needs of the province until around 2025/2030, depending on the rate of growth of consumption. A similar increment is also available from the Thukela. Thereafter, further increments will be extremely expensive as well as conflicting with users in other areas and the province should aim to cap water use and live within the available resource. Examples of the detailed projections are shown below. |

| scenarios for future water demand in the Rand Water supply area |

|

| Department of Water Affairs, Vaal River System: Large Bulk Water Supply Reconciliation Strategy, accessed at http://www.dwa.gov.za/Projects/VaalWRMS/documents.aspx |

what are we saying about water quality? |

The quality of water resources in the province is generally poor in all areas downstream of the Vaal Dam as well as in the Crocodile River catchment. This is a function of the low volumes of water, the high levels of urban, industrial and mining activity and poor management of some urban services. Key quality challenges are:

Because of the vulnerability of the Highveld catchments, special standards for wastewater treatment have long been enforced in Gauteng and surrounding areas. To achieve these, South Africa was at one stage an international leader in wastewater treatment technologies, so technology is not a major barrier to achieving standards, although it is an expensive and commercially competitive area. The present challenge is primarily one of management of existing plants and investment in the expansion of treatment capacity. |

what do we recommend? |

|