| introduction |

| the laws of attraction |

| the laws of attraction | ||

| City-regions provide – or should provide – high-end quality of life: that is their attraction. They are urban agglomerations of high-end economic activity, suburban and city dwelling, wealth and opportunity, see concentrations of professionals and higher education institutions, and offer art, culture and recreation. But those cities and city-regions also rely on the labour of workers, many of whom are denied access to precisely those amenities and outlets that make ‘city living’ desirable. | ||

|

||

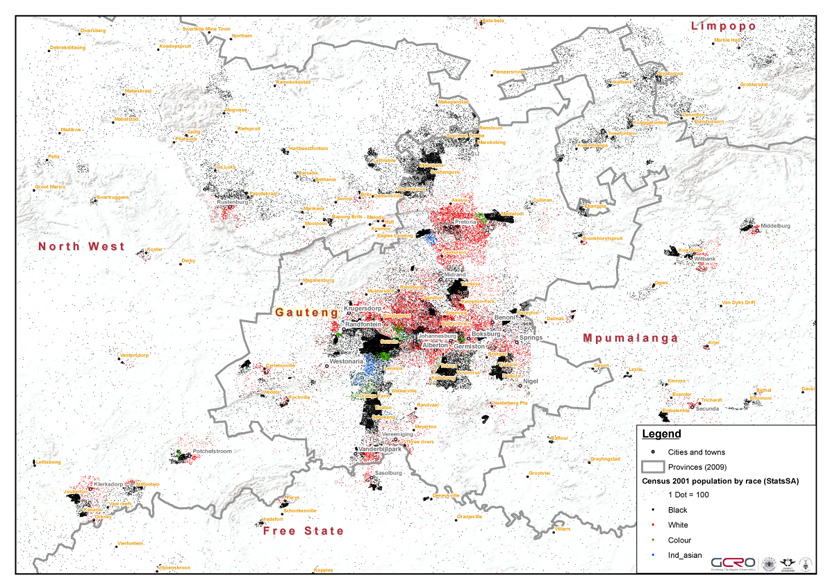

Nowhere is this inequality more pronounced than in South Africa. Apartheid tried to keep cities ‘white’ and forced black South Africans to live in townships, zoned by race, kilometres away from cities and often physically buffered by industrial belts, motorways or topography. In post-apartheid South Africa, cities and city-regions have therefore had to focus on inclusion, openness and challenging race-based inequalities, while remaining economically competitive in a context of globalisation. The Gauteng city-region exemplifies these challenges. The polycentric region of cities includes Johannesburg, Tshwane and Ekurhuleni. Measured on the basis of GDP at purchasing power parity, Johannesburg by itself is estimated to have the largest urban economy in Africa, just ahead of Cairo. The GDP of the wider metropolitan region is even larger. (http://www.citymayors.com/economics/usb-purchasing-power.html) Tshwane (formerly Pretoria) is the administrative capital of both apartheid and the democratic South Africa. Ekurhuleni is a centre of heavy industry and manufacturing. Each had – and still have – adjacent townships zoned for black, coloured or Indian citizens, and the map at the bottom suggests that movement out of these areas and the creation of more integrated residential areas has taken longer than perhaps anticipated, and the physical separation of people – on the basis of race, combined with class as black elites have moved out of townships and into formerly white suburbs – remains a key challenge. Moreover, as economic conditions have hardened with the global economic crisis coming hard on the heels of the oil price peak and a sharp rise in domestic interest rates, the Gauteng city-region has acted as a magnet for people living in poorer parts of the country, and the region more broadly. As a result, the population of the Gauteng province grew by 1 278 211 between 2001 and 2007, a 13.6% increase. So when we ask about the quality of life in the GCR, the issue should be understood in context: a large, fast-growing polycentric city-region, built on early foundations of the gold found on the Witwatersrand (the ridge of white waters), covering a large spatial area, attracting people from across the African continent, but in a developing country that is among the most unequal in the world and which only became a democracy 16 years ago. These are not excuses: they are context. |

||

| population distribution by race across the GCR according to Census 2001 | ||

|

||